FAIR Components of Scientific Models

Consider “basic theories” that are particularly simple in two ways.

First, they describe selected aspects of material objects, abstracting from all other properties – homogenous samples, thermally isolated containers, points, rigid solids, infinitely thin layers, etc.

Second, they provide particularly simple expressions and means of combination for their simple objects. For example, the theory of electric circuits has basic elements such as resistors, batteries, and capacitors, described by simple expressions like \(RI\) or \(q/E\), with sequential chaining of resistors \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) described by summation: \(R_1 I + R_2 I\).

Scientists use multiple basic theories to construct models because physical systems are usually too complex to be effectively described by application of a single theory. In most cases, observed behavior can only be explained when we consider many types of interactions by combining different theories and applying them jointly to a complex structure.

In equation-driven analytical modeling, one uses basic theories as “FAIR components” of the model. Simple objects are identified, expressions are accessed, and these expressions interoperate via arithmetic combinators in systems of equations.

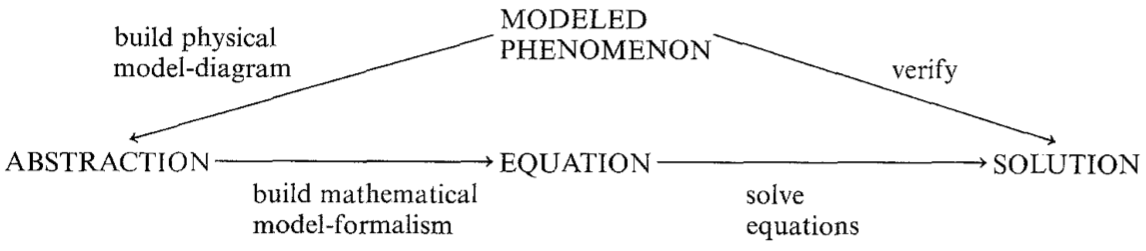

Żytkow and Lewenstam, in “Analytical chemistry; the science of many models” (1990), go into depth on what I’ve outlined thus far (I highly recommend it!), and the diagram below showcases this equational-model-building process:

I believe that data-driven computational modeling has a lot in common with equation-driven analytical modeling. Just as analytical modeling benefits from the interoperable combination of basic theories, computational modeling can benefit from available digital resources that are unambiguously scoped – via metadata – as applicable to particularly narrow objects, situations, and processes.