Deconstructing the Database, Propagation Networks, and Tuple Spaces

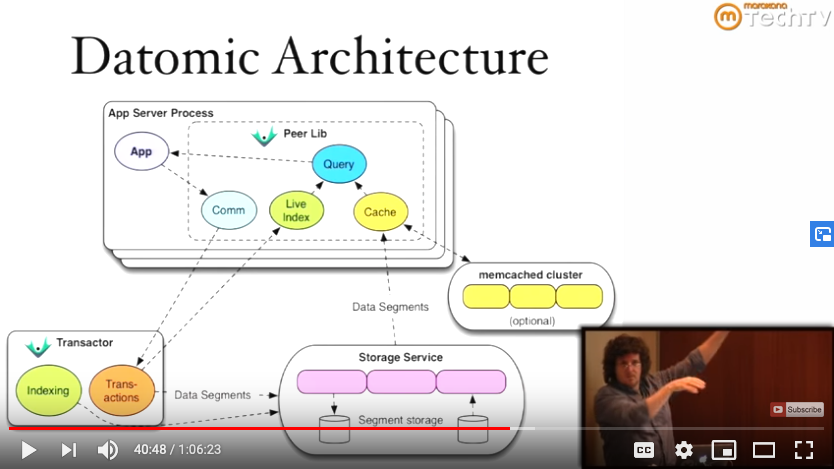

I enjoyed Rich Hickey’s talk on deconstructing the database, whereby he shows an unbundling of the concerns of transaction processing and durable storage from the concerns of a query engine, of live indexing, and of caching. Rather than have all concerns integrated in one server process for database management, the transaction processor is a separate service, the transactor, and durable storage of data segments/blocks is also a separate service with a key-value-store interface. See the screenshot below, which links to the full one-hour talk.

Slide of Datomic architecture, from Rich Hickey's talk, Deconstructing the Database.

Slide of Datomic architecture, from Rich Hickey's talk, Deconstructing the Database.The Datomic architecture is well-suited for read-heavy workloads. If all server nodes bundled all database functionality, then any node could process transactions, and thus scale writes, but then one has to address the complexity of distributed transactions. In the Datomic model, there is a single transactor, but there may be several reader processes, each of which has a local cache of the shared durable storage.

The shared durable storage also simplifies things, because although this architecture is not shared-memory, it also doesn’t go as far as shared-nothing. It is more akin to shared-disk, as if all reader nodes were connected to an attached RAID. Given that this shared storage is treated as a key-value store, the implementation is flexible: a supercomputing center’s shared project filesystem, AWS S3, Postgres, DynamoDB, whatever.

Key enablers of this architecture are (a) immutability of the data and (b) a simple information model, that of tuples representing assertions and retractions of simple entity-attribute-value statements, each with an associated transaction entity (where a key attribute of this entity is a timestamp value). This means that persistent data structures can be used in merging new data with old data – lots of on-disk structure is shared, and with maximal granularity because there are no schema migrations.

Relation to Propagation Networks

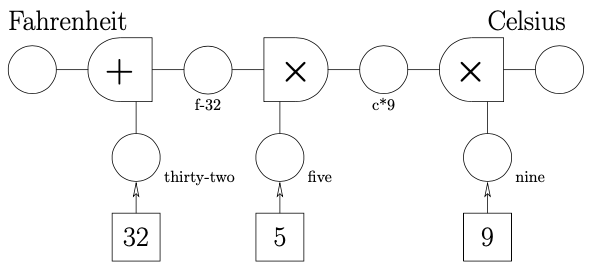

In Alexey Radul’s Ph.D. thesis, propagation networks are detailed as a flexible and expressive substrate for computation. The idea is that a collection of propagators act on durable memory cells that accumulate information. For example, the figure below from Radul’s thesis depicts a multidirectional temperature converter that embodies the formula .

A multidirectional temperature converter.

A multidirectional temperature converter.The formula is a relation, not simply a function, and the propagators are relational as well, reading from attached cells and also writing to them in order to propagate information. In the network above, the cells are depicted as circles, and there are some propagators – depicted as squares – that are rather simple in that they just output a constant value to any attached cells.

Cells in propagation networks accumulate information, so their semantics as data stores are like the immutable durable stores of Datomic rather than e.g. the update-in-place B+-trees of many database systems. Thus, I can envision a propagation network architecture where each cell maps to a pair of (transactor, key-value store) corresponding to a Datomic store, and each propagator maps to an “app server process” as depicted in the Datomic architecture slide above, connecting to one or more Datomic cells and propagating information among them as per its locally-installed logic.

Relation to Tuple Spaces

The tuple space model of parallel programming, as for example embodied by Linda1, is one where a multitude of processes pull and push to a common pool of information represented as tuples. This model seems to map well to the Datomic model, particularly when extended to a large space of stores and processors as in the propagation network vision.

If an additional component identifying the cell is added to the information model, making each statement a 6-tuple rather than the 5-tuple of datomic (entity, attribute, value, transaction, and assert-or-retract), all information can be pooled in a common tuple space. Furthermore, given Datomic’s immutability semantics, the complexity of blocking operations as described in the Linda paper can be traded for that of ensuring valid-for-this-transaction reads, which is already a first-class concern of Datomic queries.