Towards a Materials Ontology With Protégé

I decided to build on my “20 queries” exercise and draft a partial ontology for materials using Protégé, an open-source ontology editor. I’ll focus discussion here on named restriction classes for materials. For example: what materials belong to the Zintl phase?

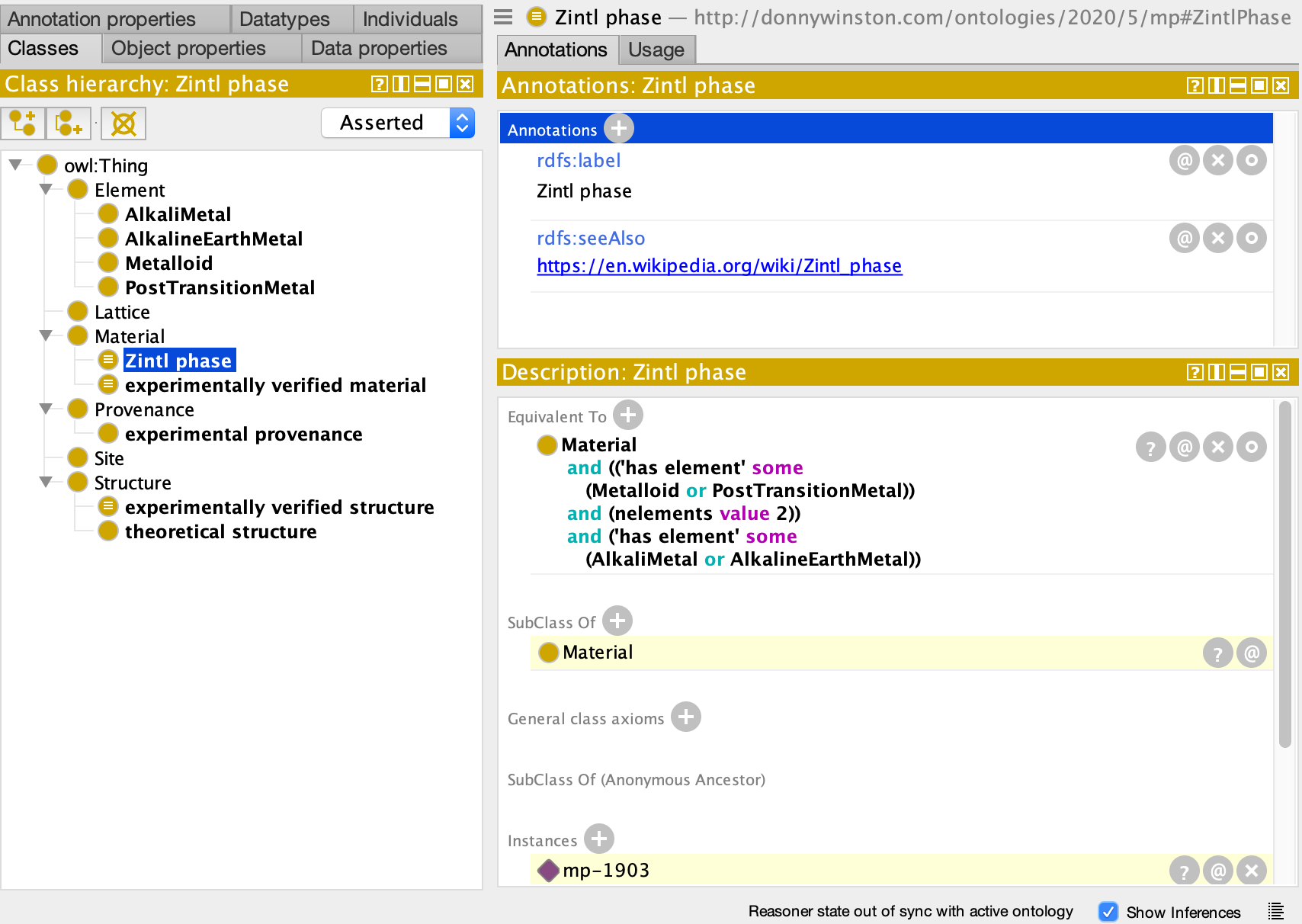

Below is a view in Protégé1 detailing the :ZintlPhase2 class:

I annotated the URI for the ZyntlPhase class with a readable rdfs:label value, so

Protégé displays this instead. I also annotated the class with a rdfs:seeAlso value pointing

to a Wikipedia page.

Rather than pinned merely as a so-called “primitive” class in a pre-defined hierarchy, the ZintlPhase class is defined as equivalent to a class that satisfies certain restrictions. This is a bit more powerful than defining an anonymous class and then giving it a name, because in the latter case you still need to produce instances of your named class through its constructor.

With an ontology such as this, you can run a reasoner over your data and infer not only what restrictions must apply to instances annotated as belonging to a class, but also infer class membership by noting satisfaction of necessary and sufficient conditions. In this case, the material mp-1903, containing aluminum and barium, has been inferred (yellow highlighting) to be an instance of ZintlPhase.

One notable aspect of OWL ontologies highlighted by this example is their Open World Assumption.

The some keyword shown in the screenshot above sets an

existential restriction3. A Zintl phase material must have an element that

is a metalloid or a post-transition metal. It also must have an element that is an alkali metal

or an alkaline earth metal.

If I had not included the value restriction on a separate property,

that the number of

elements nelements is 2, and

instead tried a cardinality restriction of 2 on the ‘has element’ property, the reasoner

would not infer any materials as Zintl phases. This is because of the Open World Assumption:

just because the data for a material includes only two ‘has element’ assertions, perhaps there

is another assertion not in the current data set that will eventually make its way to us.

Of course there are ways to “close” things – including the use of so-called closure axioms –

but “open by default” is the OWL way and is attractive for data interoperability.

The ontology also defines an ’experimentally verified material’ equivalent class that lays

bare the logic behind inference of what might otherwise be a denormalized key-value pair

associated with a material. The equivalence is a Material with some Structure that

is experimentally verified. In turn, an ’experimentally verified structure’ is a Structure

with some experimental provenance. Finally, ’experimental provenance’ is a primitive

subclass of Provenance (notice how it has no white stripes in the screenshot).

URIs are given for ICSD IDs, and some of these resources are instances of ’experimental provenance’ (some ICSD IDs are for theoretical studies). Material mp-1903 has a structure that in turn has some experimental provenance (three matching experimental ICSD IDs ), so it is inferred4 to be an instance of ’experimentally verified material’ in Protégé.

I have merely explored some ideas about a materials data ontology based on my “20 queries” exercise. This demo ontology is by no means complete or even recommended as a basis, but I hope it’s helpful to illustrate some options for modeling in RDF and OWL via Protégé. Here is the demo ontology in full.

References

Protégé Desktop v5.5.0. https://protege.stanford.edu/. ↩︎

http://donnywinston.com/ontologies/2020/6/mp#ZintlPhase. ↩︎someis Protégé shorthand for use of theowl:someValuesFromproperty of anowl:Restrictionclass. ↩︎I used the FaCT++ 1.6.5 reasoner in Protégé, but choice of reasoner shouldn’t matter for this example . Several reasoners are available via Protégé’s built-in plugin registry. ↩︎