Worse Is Better, and the Rule of Least Power

There are a number of reasons to punt on power in a design, to go with a worse-is-better style such that you express the design in the least powerful way.

Worse is Better

The phrase “worse is better” comes from a talk by Richard Gabriel on the topic of software specification.1 He introduces and compares two philosophies of design, one he labels “the right thing”, and the other he labels “worse is better”; he also uses labels referring to where exemplary systems for each philosophy originated, but I’ll refer to them here as the right-thing and worse-is-better styles.

The worse-is-better style says that it’s okay to put more work on an end user if it means less work for the implementer: “It is more important for the implementation to be simple than the interface.” It’s okay to leave things out: “completeness must be sacrificed whenever implementation simplicity is jeopardized,” whereas for the right-thing style, “simplicity is not allowed to overly reduce completeness.” As for consistency, in the worse-is-better style, “the design must not be overly inconsistent”, whereas for the right-stuff style, “consistency is as important as correctness.”

Worse-is-better is about a design that is maximally usable for a range of implementers/operators while still being at least sort-of-okay for end users of the deployed implementation/system:

“C is…a language for which it is easy to write a decent compiler, and it requires the programmer to write text that is easy for the compiler to interpret…Both early Unix and C compilers had simple structures, are easy to port, require few machine resources to run, and provide about 50%-80% of what you want from an operating system and programming language…Half the computers that exist at any point are worse than median (smaller or slower). Unix and C work fine on them. The worse-is-better philosophy means that implementation simplicity has highest priority, which means Unix and C are easy to port on such machines.”

An important property of worse-is-better designs is that they can and sometimes do become better over time, potentially serving as disruptive innovations:

“It is important to remember that the initial virus has to be basically good. If so, the viral spread is assured as long as it is portable. Once the virus has spread, there will be pressure to improve it, possibly by increasing its functionality closer to 90%, but users have already been conditioned to accept worse than the right thing. Therefore, the worse-is-better software first will gain acceptance, second will condition its users to expect less, and third will be improved to a point that is almost the right thing.”

The Rule of Least Power

Tim Berners-Lee elaborates on a similar idea for choosing a programming language:2

“The low power end of the scale is typically simpler to design, implement and use, but the high power end of the scale has all the attraction of being an open-ended hook into which anything can be placed: a door to uses bounded only by the imagination of the programmer.”

However,3

“There is an important tradeoff between the computational power of a language and the ability to determine what a program in that language is doing…if you capture information in a simple declarative form, anyone can write a program to analyze it in many ways…the less powerful the language, the more you can do with the data stored in that language.”

In other words, the more constraints you place on the power of what you deploy to end users, the more you empower those end users to predictably build upon what you’ve delivered:

“weather information conveyed by an ingeniously written [app]…might provide a very cool user interface or other sophisticated features, [but] the results of the program will not usually be predictable in advance. A search engine finding the resource will have no idea of what the weather data is or even, in the absence of other information, that it is a weather-related resource. The only way to find out what [an app] means is generally to set it running, and see what it does.”

Note that leveraging the predictability of what you deploy may not be in a given end user’s skill set – it may not be a familiar activity, i.e. it is not (yet) “easy” for them, despite the simplicity of the offering.4

As Simple as Possible, but No Simpler

What is the appropriate “least power” for a system? A system needs to support expression of simple explanations and predictions. Alan Kay talks about how circles are not powerful enough to explain planetary motion simply.5 “Planet” means “wanderer” in Greek – the motion of planets was a mystery for centuries. Copernicus’s scheme – with the sun in the center of the solar system rather than the earth – made things more tractable, but it was still a mess of circles. Kepler made it simpler by going for slightly more power via using ellipses rather than circles – ellipses were an appropriate least power, finally supporting simple explanations and predictions:

“You get simplicity by finding a slightly more sophisticated building block to build your theories out of.”

It is often desirable to scale power. For example, consider models of a water molecule with different levels of expressivity, i.e. different levels of explanatory power. One model could express only chemical composition, that there are two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, i.e. “H2O”. A more powerful model could express logical structure, i.e. “H-O-H”. An even more powerful model could express physical structure, i.e. the angle between two H atoms bound to O and the relative size of H and O atoms. As elaborated in 6:

“Just because one model is more expressive than another does not make it superior; different expressive modeling frameworks are different tools for different purposes. The chemical formula for water is simpler to determine than the more expressive, but more complex, models, and it is useful for resolving a wide variety of questions about chemistry. In fact, most chemistry textbooks go for quite a while working only from the chemical formulas without having to resort to more structural models until the course covers advanced topics.”

Power scaling may be idiomatically encouraged within a more powerful language, and may even be explicitly standardized.3 For example, JSON is a standardized use of a subset of the syntax of JavaScript.

Less Power via Functional Programming

Functional programming (FP) may be seen as a discipline to scale down power relative to object-oriented programming (OOP). Rafael Dittwald7 characterizes FP and OOP via their respective takes on the expressive power of referencing mutable state, mutating state in place, and side effects. While powerful, these techniques can be confusing and difficult to reason about. OOP’s stance is not to constrain, but rather to organize, whereas FP’s stance is to minimize, concentrate (reduce the number of places where they occur), and defer (have them happen later in a process, preferably via an underlying system/runtime rather than via custom code). The tool in OOP to organize state is objects, and a program can be seen as an interaction of agents. The tool in FP is functions, and a program can be seen as a pipeline of input to output.

Less Power via Plain Data

Plain data is less powerful that even “pure” functions - no behavior is expressed. Often, data rather than code can be used to define/drive control flow. This is data-driven programming, aka configuration-driven programming.

In “Transparency through data”, James Reeves8 posits that to build on something, that something must be seen clearly: it must be transparent. Transparency is about understanding, and understanding is about prediction. Code that’s easy to predict is transparent. In particular, the broader the predictions we can make, the more transparent the code is. What makes something predictable? Constraints. The more we constrain something, the broader the predictions we can make about it. By empowering something, we make it more opaque, less transparent:

“With great power comes great unpredictability.”

Imagine this “function” in Python defined using a dictionary:

NOT = {True: False, False: True}

NOT[True] # False

NOT[False] # True

Both the domain and co-domain of this function are transparent. It’s clear on inspection what input corresponds to what output. There is no additional behavior, no function body, to interpret. It is predictable.

Regular expressions are the ellipses of text search. They are more sophisticated than plain strings, but less powerful than code. Actually, a regex is still quite powerful due to backtracking, and is guaranteed to halt only “eventually”. RE2 supports a more constrained form of regex, e.g. with no backtracking, guaranteed to halt in linear time. Less powerful, more predictable.

Regular expressions are an example of a domain-specific language (DSL), a great technique for deliberate downscaling of power. A language has syntax and grammar, primitives and means of combining them, and a DSL can be expressed in plain data. Regular expressions are a DSL for text search expressed as plain string literals. Datalog is a DSL for database querying using plain scalar and collection literals. The MongoDB languages for collection filters, projections, and aggregation pipelines are all expressed as plain JSON.

Worse-able Environments: Tuning Transparency

If you want to use the least power necessary to solve a given problem, but you don’t want to switch programming environments all the time, you want a worse-able environment, one that supports worse-is-better design by helping you to self-impose constraints.

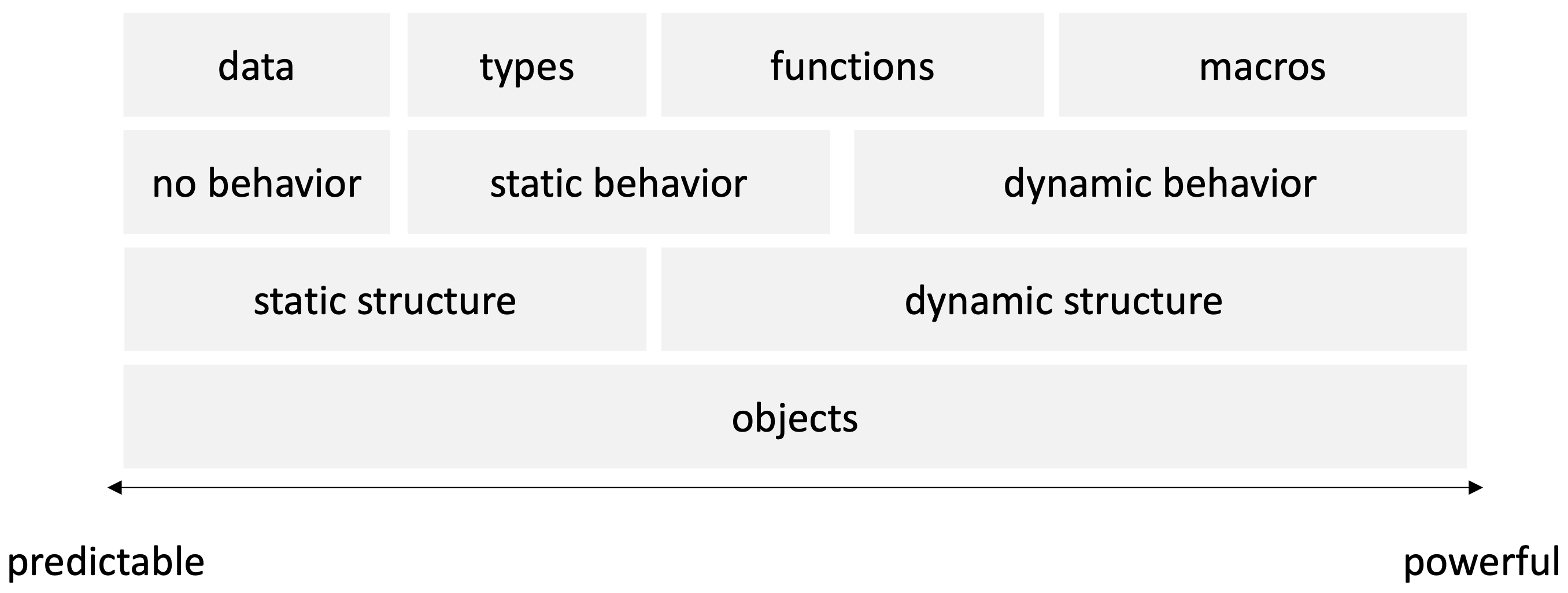

Below is my attempt at a diagram showing a spectrum of programming concepts from least to most powerful, and thus from most to least predictable. This is an elaboration of the saying, “data > functions > macros” (data over functions over macros) in the Clojure community.

Plain data is most predictable: it has no behavior, and its form doesn’t change over time. Slightly more powerful is a system that validates and conforms data types, like one enforced by a compiler or other mechanism apart from custom-written code. Such a system has some behavior (validation and conformance/destructuring), but this behavior doesn’t change over time, and the behavior is specified “under the hood”, i.e. there is no need to manually track evolving data structure from input to output as for a function.

Next along the power spectrum is functions, where one has to read code to see how data structure evolves from input to output. The behavior can be “static” in a sense of being “shallow”, i.e. with loops and recursion avoided. Limiting a function’s ability to “go deeper” can be related to transparency by analogy to transparency of a physical medium. A block of material that is relatively “clear” (an intensive property), but that has great depth (an extensive property), is less transparent because a signal through it has a long distance over which to attenuate. “If it can’t repeat, it’s not Turing complete,” yielding a less powerful but more predictable artifact.

Beyond “deeper” functions is macros, where the specification of dynamic behavior may itself may be specified dynamically. Examples of macros in Clojure include those used to facilitate polymorphism and interface protocols.

Many programming environments, by design or idiomatically, bundle one or more of the shown elements of power rather than allow their use à la carte, making it difficult to tune transparency. In object-oriented programming (OOP), for example, an object tends to encapsulate some data, situate itself in some type/class hierarchy, define static behavior/methods for operating on its data, define dynamic methods for operating on itself, and dynamically select code to execute based on type polymorphism and inheritance.

Coming Full Circle - Making Lisp “Worse”

Richard Gabriel’s example of a right-thing language is Common Lisp, and his example of a worse-is-better language is C.1 It seems that while C has gotten “better” (object-orientation in C++ and other C-like languages), Common Lisp has gotten, not “worse”, but worse-able, via Clojure.

References

Rich Hickey, “Simple Made Easy”, Strangle Loop conference (2011). (transcript). ↩︎

Alan Kay, “Power of Simplicity” (2015). (relevant five minutes: 5:45-10:45) ↩︎

“2.4 - Expressivity in Modeling”, in Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist, 3rd ed. (2020). ↩︎

Rafael Dittwald, “Solving Problems the Clojure Way”, Clojure/north conference (2019). (video, slides) ↩︎

James Reeves, “Transparency Through Data”, Dutch Clojure Days conference (2017). (video) ↩︎